Fracture Resistant Endodontic and Restorative Preparations

Written by David Clark, DDS; John Khademi, DDS, MS; and Eric Herbranson, DDS, MS

INTRODUCTION

In 1890, G. V. Black proposed both a cavity classification system and cavity preparations that remain intact and the standard of care 120 years later. The consummate scientist that was G. V. Black, we can assume, would be shocked to find today we still cling to both of his systems in spite of advances in almost everything: photoelastic studies in stress and strain, modern engineering, adhesive materials, magnification, outcome studies, the epidemic of cracked teeth, computers, the telephone, and the list goes on and on. In this article, we will explore a few cases that demonstrate the problems associated with current models of restorative and endodontic tooth preparations. The new science of strong teeth will be briefly outlined, serving as a platform for more in-depth discussions of both restorative cavity shapes and endodontic access and canal space management in future articles.

(Full article appears HERE.)

DR. HERBRANSON

The X Factor—Anatomy

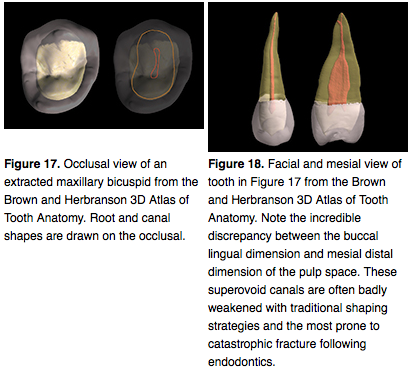

A casual observer of tooth anatomy may think that most roots have a round cross section. The reality is that most roots are ovoid. How ovoid depends on the specific tooth; for instance, the upper canine root at the cervical line is 5% wider facial lingual than mesial distal, whereas the lower canine is 9% wider. The lower incisors are about 7% wider. The upper premolars show the largest differences at about 30% wider facial lingual than mesial distal at the cervical cross section. The pulp chamber and canal shapes mimic the external shape of the tooth because dentine is laid down at a constant rate during tooth formation. So an ovoid root form will predict an ovoid pulp chamber, but the pulp chamber will proportionally be much longer and narrower that the external shape. For instance, an upper second premolar with an external mesial distal versus facial lingual difference of 40% could have a 400% difference in the pulp space. This configuration would carry much of the way down the root. This is common and somewhat obvious in lower anteriors and upper premolars, less obvious in canines, and common but not obvious in molars (Figures 17 and 18).

Complicating this picture is the presence of concavities on many root forms, which effectively elongates the pulp spaces as well as changing their geometry from ovoid to kidney bean-shaped. These concavities are found on almost all teeth to some degree. Upper and lower premolars, lower anteriors, and all molars have varying degrees of root concavities that affect the internal size and shape of the pulp and upper canal shape. For example, the distal roots on lower molars and the lingual roots of upper molars frequently have significant concavities that are not obvious on conventional radiographs and are not well understood by most practitioners. This morphology can dramatically affect the appropriate treatment protocols. The one positive in this picture is that the canal space in the apical third tends to be round. The principles of dentine conservation require all these anatomy variations be taken into account when shaping the canals, during obturation and when placing restorative.

Continue reading the full study HERE.

Thanks for visiting Modern Endodontic Care of San Leandro, CA.